But welded onto it is a game about hopping from planet to planet whilst pursued by space gits, facing increasingly stern challenges to your engineering skill, and I’m not altogether certain what to make of it. On the one hand, it’s brutally difficult, and often in the most frustrating ways. But on the other hand, it’s an elegant piece of game design that manages to add impetus, strategy and tension to an otherwise aimless physics sandbox. It’s a roguelite whose purpose is to force you to get better at using a toy, and the more I smash my head against it, the more I think I like it. You’ll spend most of your time in Nimbatus on the drone edit screen, which is a blueprint onto which you drag, drop, connect and calibrate the pieces of your drones. Starting from a central core, you can use as many components as you like in sandbox mode, or as many as you’ve acquired so far in campaign mode. Any component that does a thing - such as a gun or a thruster - can be assigned an activation key on your keyboard so you can control it in flight. And of course, that activation key can be simulated - that is to say, activated by the output of a switch, a sensor, or any number of devilishly complex logic components. But that’s not something you need to worry about at first. A functional drone can be as simple as four thrusters mapped to WASD, and a fuel tank. (Or it can be the fucking SHATTERPILLAR, my proudest creation to date, which uses crude automation and audio components to do… this. Make sure to have the sound on).

For Nimbatus’ tutorial mission, which involves flying around a planet to spot a box, you won’t need anything more than the very simplest creation. But a little thrusterbot won’t get you much further than level one. The difficulty ramps up with startling speed, presenting you with various things you must either retrieve or burst, and pitting you against both varying levels of air resistance and gravity, and an absolutely pitiless array of baddies. It starts with space bees, but in the space of a couple of missions you’ll be facing one-shot-kill missile turrets, exploding beetles, fighter drone swarms, and screen-filling, unkillable snakes.

The game does give you more to work with, at least. Completing missions awards you with drone parts, and the struggle to meet mission parameters with scarce, randomised components makes for a fresh set of engineering puzzles every time you play. Faced with an enemy packing powerful long-range weapons, and having recently acquired a couple of big armour plates, I decided to make a tank of a drone that could get in close and cut the baddies up with the short-range plasma cutters I had to hand. But I was short on thrusters, and so my eventual build was tragically slow, getting blown to bits as it lumbered across the sky. In the end, a radically different, ultra-lightweight build won the day.

And sometimes, the only way to surpass the limits of your component pool is to get complex. I’ve never been much good at computer science, and have never had any interest in building computers within computer games, despite the features being right in front of me in favourites like Minecraft and Dwarf Fortress. But when I encountered a fuel tank shortage in Nimbatus, I realised the only solution would be to use the automation components I had to allow certain thrusters to fire only when the fuel in the drone’s tanks replenished itself beyond a certain level. Similarly, when your drones get complex enough, you find you just don’t have the co-ordination - or number of fingers - to activate everything manually. Once again, in these situations, automation isn’t just helpful - it’s the difference between success and failure.

Imagine if you were woken every morning by a Turkish wrestler striding into your bedroom and putting you in a headlock until you spoke a new phrase to him in Turkish. Sure, you might have retained enough words from a long-ago holiday to evade a day or two’s grappling. But you’d be ordering a phrasebook pretty sharpish, wouldn’t you? Same with Nimbatus. Nothing makes you want to do something like needing to do it, and after a few days’ play, I was genuinely surprised both by how much seemingly-opaque stuff I’d mastered, and how intuitive it had turned out to be once I’d actually rolled up my sleeves and had a go.

Still, I can’t help but feel the campaign mode, at least on normal difficulty and above, feels a little brutal. Not the missions themselves; they’re hard, but that’s the point, right? You’re coming up with iterative, trial and error solutions to complex tasks. The problem is, the mechanic that keeps you under pressure to learn and improvise - a big baddy spaceship chasing your mobile drone factory around space, in a leaf taken from FTL’s book - also stifles your ability to iterate.

Every time you do most things in Nimbatus, you accumulate threat. Max out the threat meter, and the baddy appears and blasts one of four hull points from your ship. You can repair the hull, but doing so requires minerals you have to mine with drones while they’re undertaking combat missions, and takes from the stockpile available to spend on new combat lego. Indeed, just launching a drone depletes your mineral stock if you use more than a set number of component, and the action accumulates threat in itself. The bottom line is, the more goes it takes you to solve a problem, and the less efficient your solutions, the worse your position gets.

It’s not even a badly balanced mechanic. There are ways to mitigate threat accumulation, and it’s not that hard to manage your way out of disaster if you see your hull points as just another resource. What’s jarring is the mood it puts you under, as you end up way less inclined to try out radical long-shot builds, and instead spend hours between missions conducting simulated test flights, so as to squeeze every possible minute improvement into your stable of designs before you use them in anger. Yes, it’s “realistic”, but it hamstrings the pace of the campaign, not to mention the sense of joyful experimentation that comes so naturally from the drone creation process.

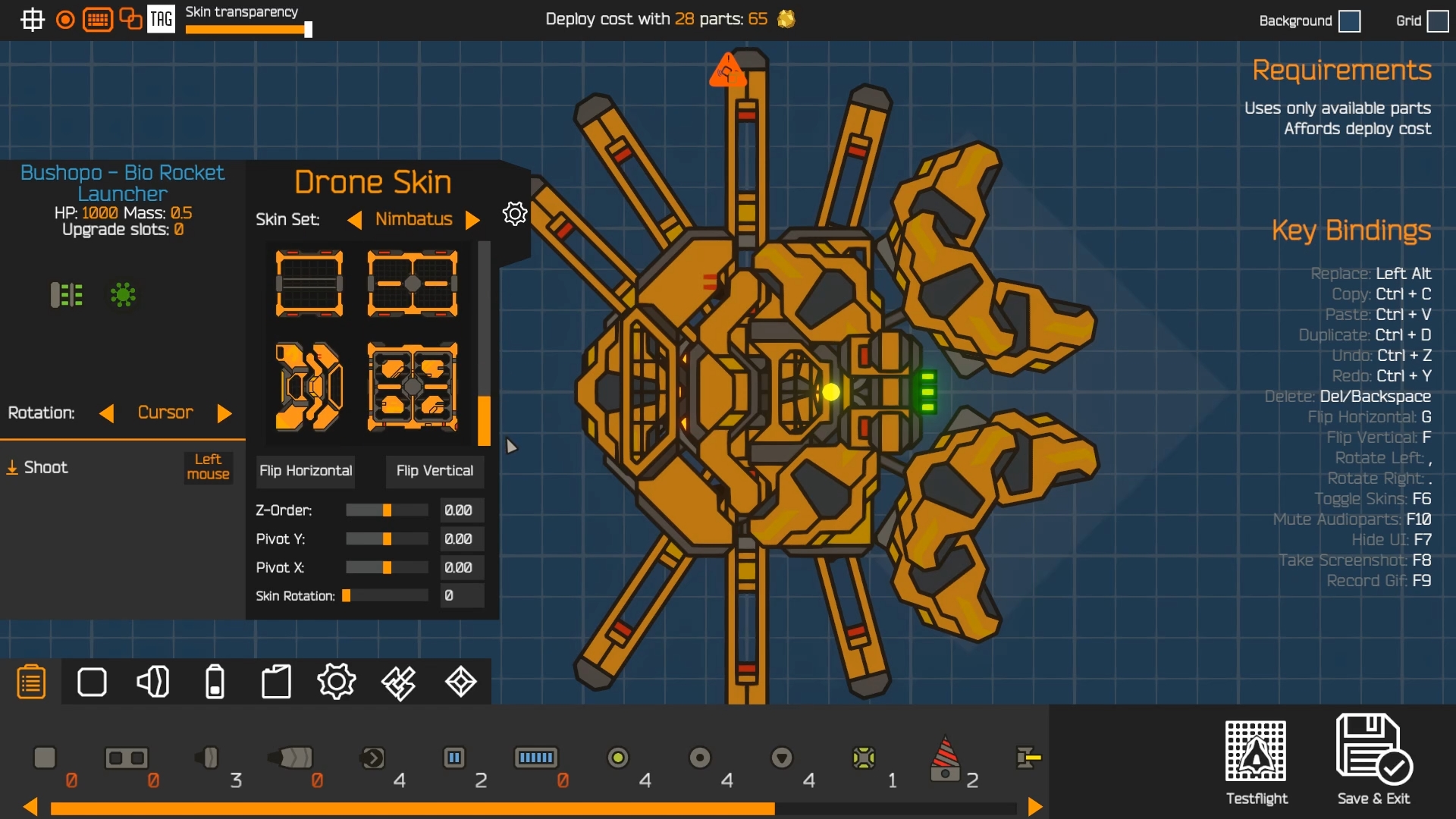

In the end, I’ve abandoned every single one of my campaign playthroughs shockingly early, and returned to the sandbox mode to muck around with the things I learned in the wars. And admittedly, I’m better every time I return. Heading back to sandbox also means I get to play with Nimbatus’ properly genius drone skin editor, which allows you to turn your drab, functional constructs into fantastic, aerodynamic things that look like Robotnik’s drinking buddies using a series of modular cosmetics. Needless to say, I made all my drones look like crustaceans. But I don’t tend to use the skins in campaign mode, as they obscure the parts beneath and make it hard to get a read on things like fuel levels and hull damage, so they’re another sandbox-only treat.

But you know what? Here’s the real masterstroke behind Nimbatus’ design. There are several sets of skins, all of which can be mixed and match to make even cooler looking flybots. But they’re all unlockables except the default set, meaning you need to play the campaign to gain access to them. And for once, the cosmetics genuinely are worth grinding for. So I guess I’m just going to have to head back to the hangar, and get better.